Advancing Subaru Hybrid Vehicle Testing Through Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation

Mr. Tomohiro Morita, FUJI Heavy Industries, Ltd.

"By adopting FPGA-based simulation using the NI hardware and software platforms, we achieved the simulation speed and model fidelity required for verification of an electric motor ECU. We reduced test time to 1/20 of the estimated time for equivalent testing on a dynamometer."

- Mr. Tomohiro Morita, FUJI Heavy Industries, Ltd.

The Challenge:

Using automated testing to develop a new verification system that satisfies the control quality level required for the motor electronic control unit (ECU) in Subaru’s first production model hybrid vehicle, Subaru XV Crosstrek Hybrid, and creating strenuous test conditions that are difficult to achieve using real machines.

The Solution:

Building a verification system with the NI FlexRIO platform that makes automatic execution of all of the test patterns possible and replicates the most severe testing environments to ensure the highest level of safety to the user, while obtaining the required control rate and meeting critical timelines.

Today, automobiles are equipped with an enormous number of ECUs to manage expanded functionality and advanced controls in the vehicle. In a hybrid vehicle, the motor ECU plays an even more complicated role as it manages the interaction between the conventional engine and the electric motor, along with its power systems.

Fuji Heavy Industries, parent company of Subaru, set out to develop its first hybrid vehicle—the Subaru XV Crosstrek Hybrid. This was our preliminary attempt to deliver a production model hybrid vehicle targeting both domestic Japanese and North American markets. Our engineers had developed a motor ECU for an earlier hybrid prototype, but the component did not meet the rigorous requirements to take a vehicle to market. For the production model vehicle, the ECU needed various control functionalities to prevent damage to the vehicle body and to ensure driver and passenger safety under various operating conditions, even scenarios that would be impossible or impractical to test on physical hardware.

For example, under icy driving conditions, a wheel can experience a sudden loss of traction. During acceleration this can cause a dramatic increase in motor speed and needs to be handled safely. However, this safety behavior cannot be physically reproduced on a dynamometer and is time consuming and difficult to reproduce on a test track. Since complex control algorithms for specific safety conditions like this need to be developed and verified, the testing needed to account for outlying operating conditions to satisfy the quality level required for a production model vehicle.

A New Approach

Our engineers connected the ECU to a real-time electric motor simulation to test and verify a variety of conditions, including the extreme outliers that may otherwise break the system in traditional mechanical testing. They developed a mechanism to sufficiently confirm this software simulation approach with three primary goals for successful testing:

● Verify ECU functionality in various conditions, including extreme environments not easily created or replicated

● Map test cases to requirements to ensure complete test coverage

● Perform regression tests with ease to quickly validate design iterations

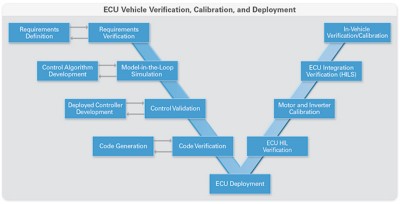

To achieve these goals, our engineering team used a V-diagram approach to launch the design and verification process (Diagram 1). The diagram describes a phased methodology for embedded software design and deployment validation, including test points at each stage. In multiple steps of the design process, the team needed the hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) system to verify the motor ECU against a real-time motor simulation that accurately represented the actual vehicle motor. Additionally, using the HIL system, our engineers could meet traceability requirements by recording test results automatically and automating regression tests when an ECU change was made.

System Success

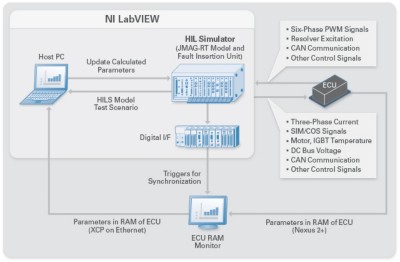

The new verification system built consists of a real motor ECU and the HIL system that simulates motor operations (Diagram 2). The HIL system can represent any operating condition of the motor by setting physical parameters such as inductances or resistances. It can also set parameters of the power electronics, including fault conditions or test scenarios such as combinations of load torque and desired rotating speed. By simply changing a parameter in the middle of the test, the HIL system can easily simulate complex test scenarios like the previous loss of traction example or even a power electronics fault in the inverter that would destroy physical hardware. When the operator requests a test pattern, the HIL system responds the way a real motor would, and the overall system response can then be cross-referenced with expectations to validate that the controller safely handles the test case.

Because the computational performance required for this process was so high, we felt National Instruments was the only supplier that could meet these requirements. We chose core system hardware based on NI FlexRIO FPGA modules, which are PXI-based controllers with FPGA chips. The modules executed a model representing the simulated operation of the motors, with all deployed programs using NI LabVIEW system design software.

We created the test scenario for sequential execution of each test pattern as an Excel spreadsheet. We set the time for execution step to 1 ms and described the test conditions, including torque and rotating speed, chronologically in the Excel spreadsheet. According to these conditions, the motor ECU operates and sends out signals, such as a pulse-width modulation signal, to the HIL system. The HIL system receives these signals then simulates operation of a real motor. More specifically, the computational process is performed and the result is an output at the same speed as the real motor. The resulting signals representing the torque and the triphase current are returned to the motor ECU.

We automated the verification process using LabVIEW to read and execute the Excel spreadsheets for the test scenarios, with obtained results written automatically to the Excel spreadsheet for the test report. The team used Visual Basic for Applications in Excel for this process.

Benefits of Choosing the NI Platform

In the HIL system, the simulation loop rate, equivalent of the temporal resolution in simulation, was a critical factor. For the motor ECU, the loop rate needed to be 1.2 µs or less for the simulator to work. Most simulation platforms from other suppliers use CPUs for computation, resulting in a loop rate in the range of 5 µs to 50 µs.

NI FlexRIO used the FPGA for control and computational purposes to meet the processing requirements, which also provided a significant advantage in terms of computational processing performance. The ability to attain the required simulation rate at 1.2 µs was the decisive factor for adopting the NI FlexRIO platform for this system. Additionally, because the NI FlexRIO has a high-capacity, built-in dynamic random access memory, we could use the JMAG-RT model provided by JSOL Corp.’s JMAG software tool chain. This made it possible to represent the highly non-linear characteristics closer to the real motor.

Moreover, our engineers could program the FPGA on the NI FlexRIO device graphically with the NI LabVIEW FPGA Module, which made it possible to develop a system with FPGA technology in a short time frame without using a text-based language such as a hardware description language.

All the test patterns developed can be run automatically in only 118 hours. Performing all the tests manually would take an estimated 2,300 hours. Automated testing also mitigates the risk and additional time associated with human errors that can occur with manual testing. The HIL system delivered additional time-saving advantages that included a significant reduction in the number of setup procedures, such as preparing a motor bench and a test vehicle, and it removed the need for test personnel to be qualified to handle high-voltage equipment.

For each test scenario, the team prepared an Excel spreadsheet reporting test results in advance, saving simulated torque and triphase current values at 1 ms time steps. The values obtained from the HIL test were sequentially written in the Excel spreadsheet and compared with the corresponding expected values to determine the test result.

Author Information:

Mr. Tomohiro Morita

FUJI Heavy Industries, Ltd.

Japan